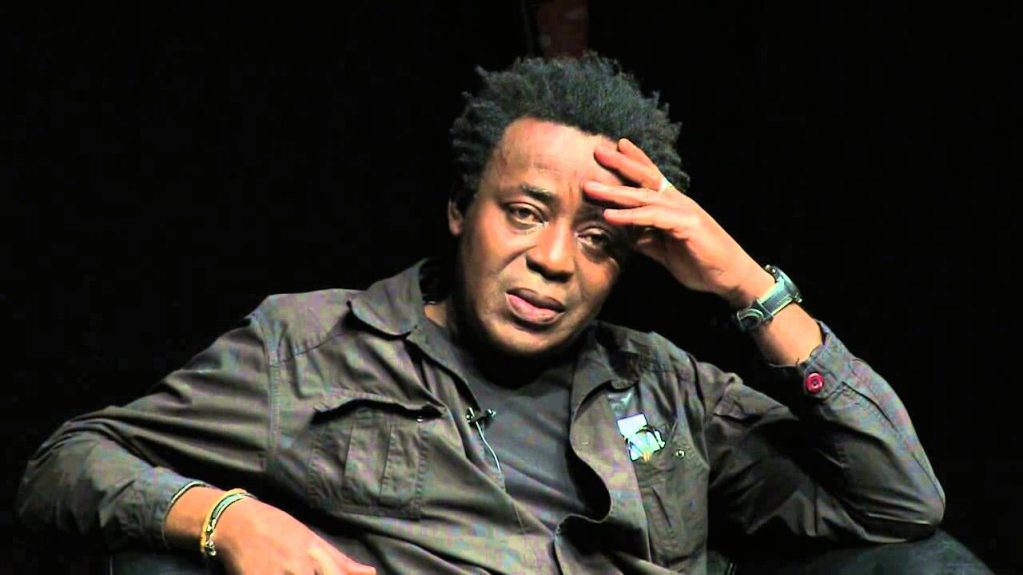

Shortlisted for this year's Artes Mundi prize, Akomfrah is known for his beautifully shot film installations tackling themes such as race, cultural identity, migration and post-colonialism

Ghanaian-born British artist and filmmaker John Akomfrah is one of six shortlisted artists for the biennial Artes Mundi prize. As well as showing his work in art galleries, the London-based artist has made films for television and for cinema release.

His major 2015 work, Vertigo Sea, is a visually arresting meditation on man’s relationship with the sea and its role in the history of slavery, migration and conflict, and was first exhibited at last year’s Venice Biennale. Shown across three screens, the work is touring the UK and can currently be seen at Turner Contemporary in Margate.

For Artes Mundi, Akomfrah is showing Auto Da Fé (2016), a beautifully shot and stylised two-screen film weaving together six stories of mass migration that have taken place over a 400-year time span.

A founder member of the Black Audio Film Collective in the early 1980s, one of Akomfrah’s first films for television was Handsworth Songs, filmed during the 1985 Handsworth race riots in Birmingham.

More recent are two films about the cultural theorist Stuart Hall, The Stuart Hall Project (2013), and The Unfinished Conversation (2012). Race, cultural identity, migration and post-colonialism are constant themes in his work, which he explores in innovative and highly poetic ways.

Auto Da Fé is the film you’re showing at the Artes Mundi exhibition. Is this the work that best represents what you’re doing at the moment?

Yes, I think so. The film is important to me because it takes questions of migranthood, which I’ve been interested in forever, in other directions. It’s about what I call the ‘microspheres of transience’, which is a very poncy way of saying something simple, which is that even lives which are formed by ceaseless movement have worlds, have microspheres. These worlds have values and meanings. And so the idea behind Auto Da Fé is to find the values behind six sets of migrant stories, stories which are formed against a backdrop of chaos. And I think that all lives lived on the edge of the precarious share certain things. It doesn’t really matter whether those communities are 16th or 18th century Ashkenazi or Sephardic Jews in the Caribbean or the Yazidi communities on the borders of Syria and Iraq. There are threads.

The film is beautifully stylised and enigmatic. A filmmaker who’s influenced you profoundly is the Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky. You’ve talked about his 1975 Mirror being particularly important to you. What is it about this film that expanded your understanding of what film could be?

For anyone who hasn’t seen it, Mirror is made of elements, and each fragment, each layer, is important to me. So you have what are essentially micro-narratives, dramatic moments: one is of a family in its evolution, another sees poetic reflections of what it’s like to live in the countryside, and then there are documentary bits about the war and what it’s like having people that you love in the war. Now, all of those elements are things that I’m interested in. And he showed you that these things, which are not necessarily legitimate bedfellows, can be brought together. You don’t have to bring them together in the way he did, but the fact that he did it at all meant it was possible. And actually, he was more than an influence. He provided many of filmmakers with a universe of possibilities, a kind of solar system that we’re still using to navigate by.

You’ve also talked about the impact of cultural theorist Stuart Hall on your thinking – indeed you’ve made two films about him. In terms of ideas, his influence was there from the start, wasn’t it?

I think Stuart’s impact on my generation was considerable. I can’t think of a black British figure who I came of age with, and whose writings or work I respect, who didn’t feel some proximity to the ideas of Stuart. And even if they rejected some of it, ideas like his idea of hybridity [in post-colonial discourse], they always had to reject it in dialogue with Stuart’s work.

You cut your teeth as a filmmaker in television, yet you recently said that you don’t think black people have any more ownership of the media than they did when you were growing up. Why do you think that black representation has failed?

I don’t know… well, I do, but it’s too long for what is essentially an interview [laughs]. Let’s just say this: there seems to me to be a difference between participation in something and having a stake in something, that is of owning it. The ownership questions I’m talking about were questions of empowerment. I mean, can you say what you want to say about being black and British in television now? I think, no. I think those who want to explore those questions now have to go elsewhere. It just doesn’t feel to me as if post-migrant communities in this country have any ownership claim on any part of television at the moment, and there was a time when it felt like it did. If you think about those departments, and both the BBC and Channel 4 had them at one point – Afro-Caribbean units, Asian units. These were creative hubs where people were hothousing ideas, and a lot came out of those units. There was a multicultural unit at Channel 4. It was one of the oldest of the Channel 4 departments. It’s gone.

You’re in the process of making a film about the Black Panthers. Tell us a bit about this. Is it fictionalised or a documentary?

Sections are fictionalised, sections are re-enacted, sections are interviews. We’re still gathering stuff. At the moment, because the resources we’re putting in are ours [with his production company Smoking Dogs Films] we can decide exactly which bits will become the thing. And we’re still adding to it. I think all material at some point tells you naturally and logically their best form.

So it could be in an art gallery. Or it could be in a cinema.

Yes. [Laughs] I’m trying not to make the job too hard for myself by deciding in advance.