A Christmas painting that speaks of anxiety not joy.

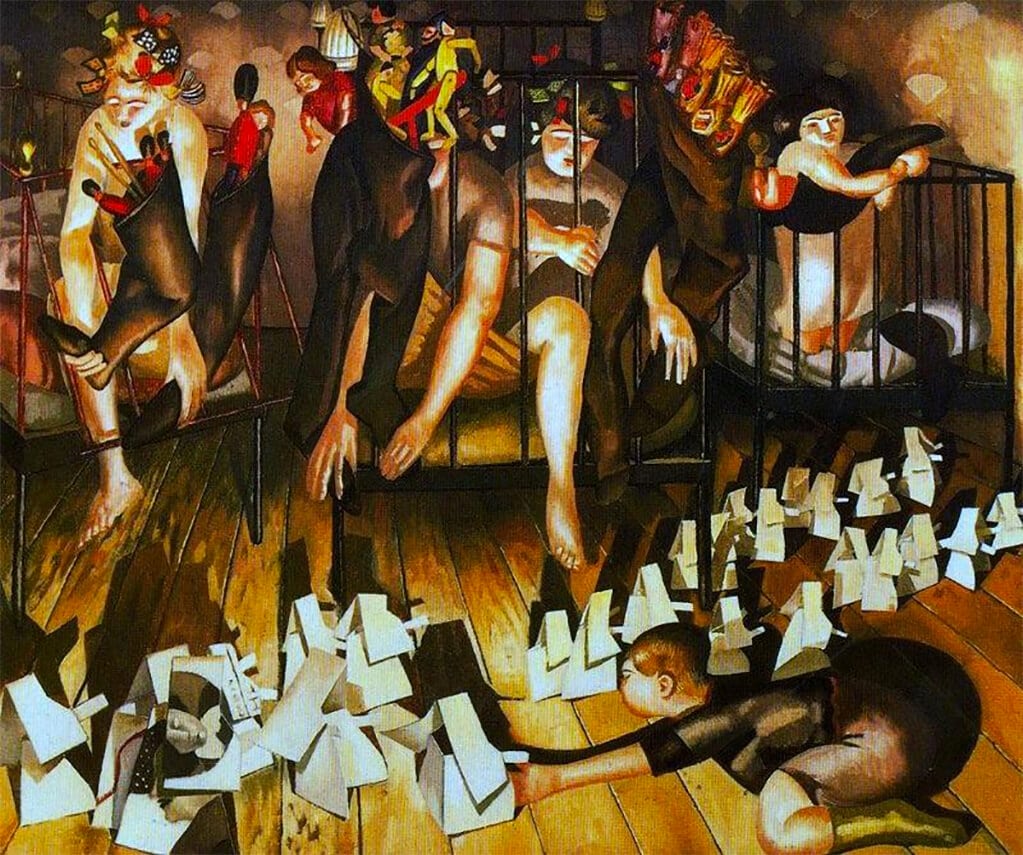

Even by his own eerie-peculiar standards, this is a perturbingly odd painting by that gifted English eccentric Stanley Spencer. It’s the night before Christmas and Christmas stockings hang from each bed frame: in this case, long rubber boots and saggy-bottomed Long Johns. And before we even consider what the occupants of each bed are up to, look closely at the heads of some of those toy figures: their painted grimaces are the thing of children’s nightmares.

We all know that while little boys and girls sleep – and unbeknown to the adults of the house – toys take on a sinister life of their own. Or at least that’s the thrill and the fear of every small child with a vivid imagination. And Spencer, who, with his pudding-bowl haircut, always looked like an over-grown schoolboy and appeared to wholly lack a worldly sensibility, displayed a particularly ripe imagination in his work, recreating biblical scenes set in his home village of Cookham, Berkshire, and often populated by local characters.

But if you imagine there’s anything remotely cosy about Spencer’s homespun holy visions, then you’ve simply never looked hard enough. His scenes rarely offer straightforward biblical narratives, but are often unsettling, particularly in their sexual suggestiveness. Combining spiritual and sexual ecstasy isn’t unusual in the work of great artists, of course – just look at Bernini’s The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. Yet Spencer does so in an oddly comic manner which is also psychologically jarring. The Dustman (Laing Art Gallery), a painting depicting a young man clearly experiencing some orgiastic vision while his wife carries him like an overgrown toddler in an enveloping embrace, is a good illustration of this. It was on the grounds of obscenity that that painting was rejected by the Royal Academy jury when submitted to its Summer Exhibition in 1935, prompting Spencer to resign. Years later their president, Sir Alfred Munnings, initiated a police prosecution on the grounds of obscenity occasioned by another painting, Double Nude Portrait (see reference below).

And look at the strange scenario of Nursery (Christmas Stockings). While the small boy is surrounded by his strange origami, four naked or semi-naked women in colourful hair-rags sit like fleshy, lumpen rag dolls, imprisoned by the metal bars of their bed frames, through which their boneless limbs extrude. Are they somnambulists, roused by some unearthly calling? Or are they merely figments of the boy’s awakening pubescent imagination? (How strangely they handle those phallic boots…) And just what are those little paper boxes, casting their great ominous shadows (tellingly, they look like fragile paper houses) that the boy appears so preoccupied by? If you look carefully you’ll find two female faces, one in profile, the other full-face, printed on a couple of the sheets.

Spencer painted this picture in 1936, in the middle of a marital crisis. He was in the process of leaving his first wife, Hilda Carline, for Patricia Preece, the subject of many of his paintings around this time, including two works painted in 1937: Double Nude Portrait: The Artist and his Second Wife and Self-Portrait with Patricia Preece (Fitzwilliam Museum). Both speak volumes about the nature of his difficult and unconsummated second marriage (Preece was involved in a life-long lesbian partnership with the artist Dorothy Hepworth, with whom she continued to live after her marriage.)

While those two double-portraits are painted in a realist style, and are quite brutal in their emotional rawness, Nursery, like many of his religious paintings, is more fantastical, even cartoonish. Could the boy, absorbed in his inscrutable play and surrounded by these fleshy suburban sirens, also be some kind of self-portrait?

Spencer’s bedrooms are rarely places of abandoned joy or easy intimacy. An early painting by Spencer, The Centurion’s Servant, 1914 (Tate), recounts a biblical narrative about faith and healing. But it doesn’t describe the moment when healing takes places, but the anguish that comes before it. It features a self-portrait of the 23-year-old Spencer on a bed surrounded by anxious females who are fervently praying and are clearly distraught. The room is dark and oppressive, just as it is in Nursery. And in Nursery the space is shallow, the floor tilted towards us, and the row of cage-like beds too big for the room, and the women themselves like giants.

Despite its title, Nursery (Christmas Stockings) is not a painting that speaks of the childhood joy that anticipates Christmas. It is a painting of oppressive sexual anxiety.