The Overexposed artists with pots, frocks and comforting clichés about Britain.

Imagine if broadcasters thought the only living pop star worth giving air time to was Lady Gaga. Imagine – the horror. It would be wall-to-wall Gaga for the foreseeable future. And then imagine if the only living contemporary artist commissioning editors at Channel 4 and the BBC even bothered looking at was… Grayson Perry. Imagine.

But wait. You don’t need to imagine – Perry has carved himself a big niche: as the go-to telly transvestite sociologist-cum-artist, fronting programmes trying to pin down the essence of Englishness, taste and class, and why critics seem to sneer at the type of art ordinary, honest folk seem to love. Now that Brit art is all but a distant memory, he’s become the only living artist in TV land. And with the recent opening to the public of his suburban gothic holiday horror house-cum-shrine in Essex (commissioned by Alain de Botton’s Living Architecture company and built with the architects at FAT – £850 to £1,800 depending on duration of stay, if you’re asking), naturally TV camera crews were there to capture it all: from sketched ideas to winning over the locals at a residents’ meeting to bricks-and-mortar realisation.

One can’t deny that he’s an engaging, warm and articulate TV presence – though where would he honestly be without the frocks? What’s more, he’s fascinated by our national obsessions, giving just enough insight into them not to sound glib, but glib enough for some undemanding television that prefers, to turn a ghastly phrase, “an affectionate look” at our national psyches rather than a properly penetrating one. That may sound a little unfair, but frankly all this overexposure can set the teeth on edge. Plus, there is that too-frequent retreat into cosy sentimentality he’s undoubtedly prone to – those faked-up girly chats with hard-faced Essex hairdressers and big-bosomed matrons over a cuppa. It’s all a bit Beryl Cook come to life. Being exposed to too much of that can harden the critic’s arteries.

Meanwhile, museums can be just as slavish to the popular and the populist as TV executives. And while you may argue that there’s nothing wrong with this – those griping elitist critics can seriously bog off – it does feel like the Brit soap-opera-level starriness of the artist carries much greater weight than the talent. In fact, Perry’s talent really is himself. That’s not to say there’s no merit in the objects he produces. It’s just that measured against his ubiquity the work can seem a little thin.

But just as success breeds success, being seen all over the place ensures you get invited to do more and more, and so we have yet another Grayson Perry outing. This time we find him beside the seaside at Turner Contemporary, and yet it only feels like two minutes since he had a show at the National Portrait Gallery, where he showed the various portraits he’d worked on for the Channel 4 series Who Are You? (the one where he made a broken Chris Huhne vase with penises all over it).

This exhibition is a mini survey – possibly because he’s been far to busy to make new stuff for it (though “Penis Huhne” is here). It takes us back to the Eighties when Perry was hanging out in boho Camden Town with Derek Jarman and Cerith Wyn Evans and making stilted “avant-garde” films in which he starred as his alter-ego Claire. The films have been lovingly restored by the BFI, and they’re quite fun, if a little laboured. In two, he seems to be channelling Lady Di, since he’s got the hairdo and one of those flowsy blouses – this is the early Eighties – and Diana crops up in his fantasies elsewhere, in one of his early drawings.

Later drawings show what a good draughtsman he is, but these early ones have a studied naivety, or perhaps he just learned to draw. The films themselves are fully rounded stories – one is a fantasy involving Claire being cursed with a green tail, and so she has to hunt down neon-green objects in order to break the spell. So even when he was trying to be “avant-garde” Perry’s natural gifts as a traditional storyteller, a fireside yarn-spinner, come to the fore. This is just one of the reasons why he’s so popular, and it’s a huge strength in his work. That it sometimes leads to a bit of faux-folkie glibness isn’t so much, but all power to him as a storyteller, I say.

But then he abandoned film to concentrate on pots. For years, it was almost nothing but pots. The same hoary old cliché of “subverting” an apparently genteel craft with etched drawings of tough boys in pain, of waif-children in Victorian garb, of distressed mothers and affectless suburban dominatrices. Some of the pots are lovely – “I Love Beauty” (pictured) reads one wobbly urn painted with delicate tendrils in China blue and rose red on a white glazed ground – but the repetition is numbing

There are tapestries here too. His famous Walthamstow Tapestry (detail pictured) with the suburban headscarved Madonna clutching her Gucci bag, populated by figures from “all walks of life” and stitched with all the brand names, from Armani to Ikea. On the face of it, these are quite powerful – a story of Britain that connects with religion and myth and a bigger universal human picture telling of need and the possibility of redemption, even if that’s only to be found in a clutch bag. It’s jokey, it’s obvious, and it’s tender. It’s real, man. Apparently.

But why does Madonna wear a Fifties headscarf while cradling her designer purse? OK, one shouldn’t expect literalism in a truth-telling fantasy of Britain, but this is clearly an anachronism in a way that the Chapman brothers’ Ronald McDonald Afro-“primitivist” sculptures just aren’t. Rather than “truth-telling”, it’s an anachronism that takes us back into a land of half-truths and nostalgia, and is part of Perry’s own personal mythology about his own life and about Claire.

Take another tapestry featuring lists: in Map of Truths and Beliefs, 2011, he gives us a Britain of fish ‘n’ chip shops, Eric and Ernie, the Free Press, Tom Jones, Shakespeare, the FA Cup, and all the other things that, in the words of The Sun, “make Britain great”. It’s all kind of tongue-in-cheek, but it’s also not. I mean, what happened to The Black and White Minstrel Show, the National Front, Enoch Powell and “Paki-bashing”, all also redolant of an era the work leans towards – or doesn’t any of that quite fit the bill? Let’s all dance round the maypole, why don’t we.

The work sends us up, but not really. And while we must appreciate he’s drawing on this idea of folk memory, and how it continually renews itself, the idea that Perry is some kind of acute social commentator, with something actually interesting to say, is absurd. His work is popular because it’s comforting, while only pretending to tell us things.

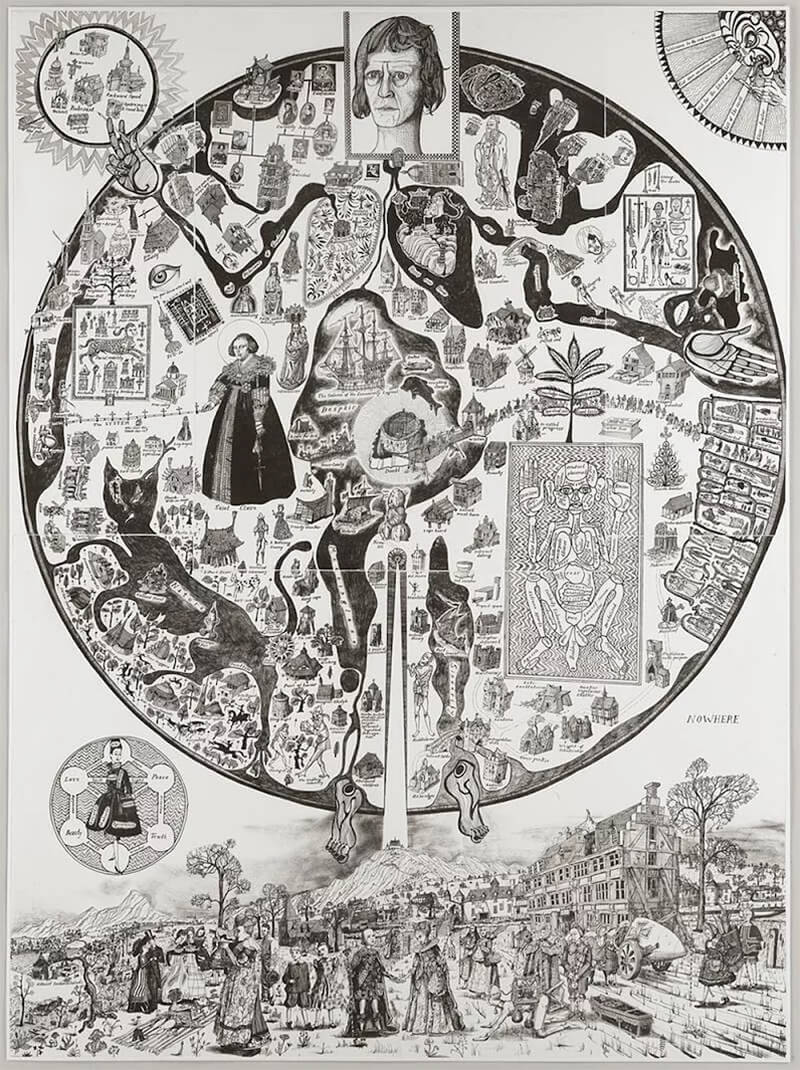

The etchings – of fantastical maps exploring British “tribes” or our psyche or whatever (see picture: Map of Nowhere, 2008) – are the best things about this show, because they’re so beautifully made (not by Perry – he just drew them, possibly, like the tapestries, on a computer).But apart from those, and apart from being an engaging TV personality, I’m reminded once again of where Perry’s talent really lies. He’s a terrific curator. His British Museum show, The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman, for which he’d gathered objects from the museum’s collection, was both delightful and fascinating, as have been his curating efforts elsewhere. And while this is an enjoyable enough show of his own work, I think we could all do with a rest now.