A joyous exhibition celebrating the artist's long and fruitful career as a printmaker.

David Hockney has been a printmaker for almost as long as he’s been a painter. From one of his earliest ventures into print, a self-portrait colour lithograph aged 16 while at Bradford College of Art (the black pudding-bowl hair emulates early hero Stanley Spencer, before Hockney went for the striking platinum-blond look), the two activities have been given equal weight throughout his career, though this, as it turns out, was mainly by accident.

Being a penurious student at the Royal College of Art in 1959, and finding that he had to pay for his own painting materials, Hockney was drawn to the print department which supplied equipment and materials to students for free. And so began his adventures in print, which have seen him experiment in a wide variety of print media.

This exhibition celebrates his work as a printmaker across those decades, from that highly accomplished self-portrait of 1954, to the very early etchings of the Sixties, and then on to his experiments with colour photocopy-printing in the Eighties and finally computer-drawing, a laborious and impractical method when Hockney started in the early Nineties, but now made quicker – as quick as applying a pencil to paper – with the advent of the iPhone and the iPad. (However, none of the iPad drawings, which were shown to such dazzling effect at his 2012 Royal Academy exhibition, A Bigger Picture, are shown here, perhaps because they’re much closer to the spontaneity of drawing than traditional printmaking).

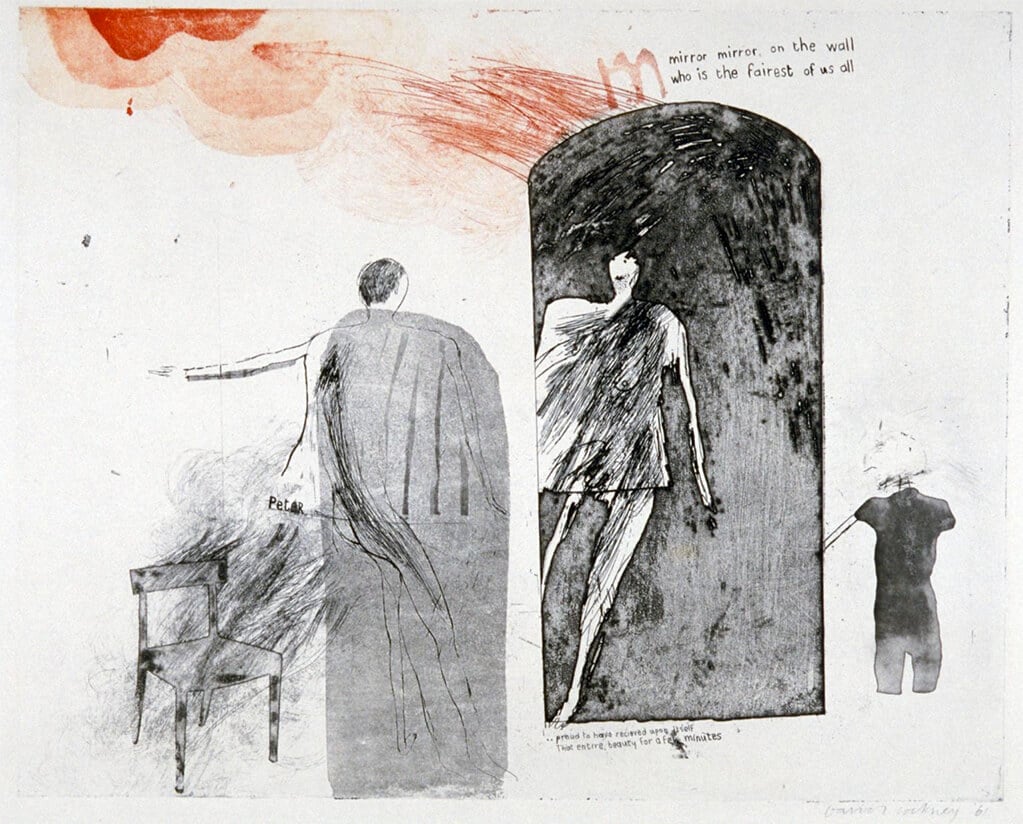

It was Hockney’s early etchings while still a student at the RCA that helped make his name, through works such as Kaisarion with all His Beauty, and Mirror, Mirror on the Wall (pictured), both allusions to poems by Alexandrian poet C.P Cavafy, who also influenced a later series by Hockney depicting naked gay lovers while male homosexuality was still illegal in Britain. While the later Cavafy prints are largely naturalistic, the two earlier works, both dated 1961, possess all the delicacy of line and imaginative playfulness of Klee, coupled with the figurative imagery reminiscent of Art Brut artist Jean Dubuffet. Hockney’s use of text also suggests graffiti.

These works in themselves don’t appear particularly narrative-driven, though Hockney is an artist inspired by words and stories. Print-making, he’s said, gave him the opportunity to work serially, in a way he felt he couldn’t as a painter. We find etchings inspired by both Picasso’s The Blue Guitarist and Wallace Stevens’ great poem The Blue Guitar, in turn inspired by Picasso’s painting. A fine portrait of the poet appears surrounded by various motifs including a guitar.

His 16-series etching, A Rake’s Progress, 1961-63, is a modern retelling of Hogarth’s eponymous set of eight prints relating the story of a young man’s moral corruption and descent into despair and madness. Hockney naturally dispenses with the tale’s moral purpose and humorously reframes it as a young man’s adventures in New York, giving himself the title role.

As he makes his way through a sequence of encounters, the series finds him firmly establishing himself as an artist (with the sale of a print to MoMA), taking in a bit of sight-seeing, going to a gay bar and observing the back view of an identikit row of cool young men in clingy T-shirts, all listening to radio transistor headphones, which were not yet available in Old Blighty. In Hockney’s hands A Rake’s Progress becomes a tale of self-actualisation.

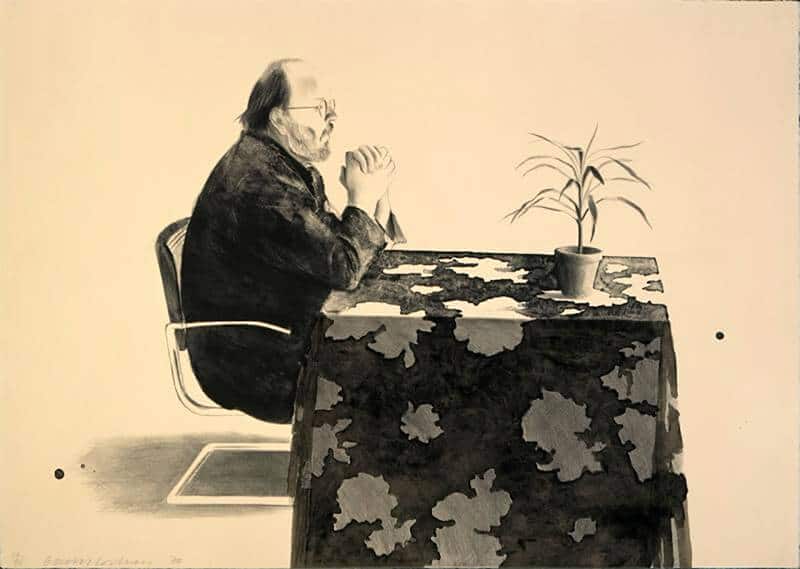

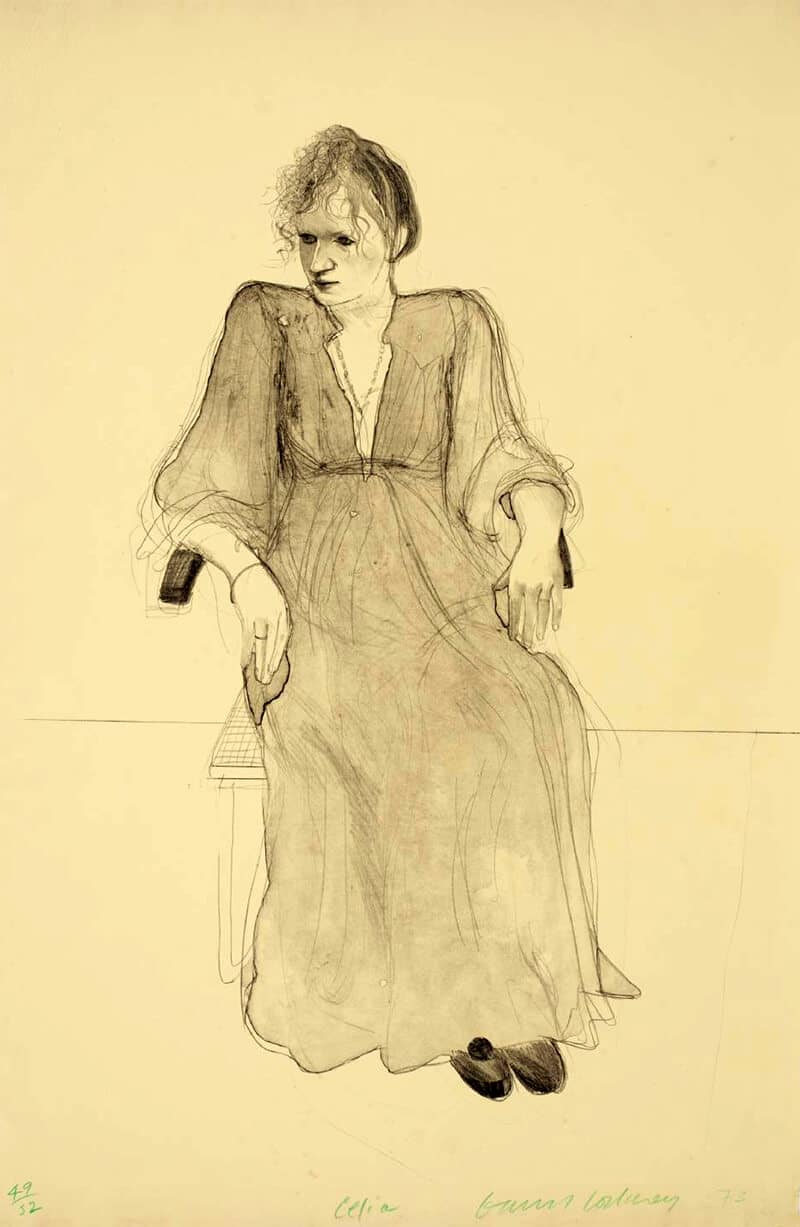

Particularly impressive are the soft, velvety lithographs, a medium Hockney returned to many years after his first foray in the mid-Seventies, portraying friends and lovers. Peter Schlesinger, former lover and muse, looks at us with a solemn, liquid gaze in an arresting bust portrait, while fashion designer Celia Birtwell (pictured) sits in a chair with her head half turned, beautiful and pensive, the sweeping lines of her dress lending the image heightened yet delicate sensuality. Henry at the Table (pictured) shows the American art historian and curator Henry Geldzahler sitting in profile at a table, his fat hands clasped in front of him in line with the fragile-looking pot plant opposite, whose symbolism seems apparent. Hockney is great at capturing mood and expression in a face, even when we can’t see much of it.

As we progress through the decades, colours become bolder, richer, hotter. They sing out, but sometimes shriek. A series of lithographs of a hotel garden in Mexico captures the intense heat, though a few make you wince with their harsh, garish notes.

I’m not so keen on the faceted multi-view images of the Eighties, which seem to me to be superficial reruns of Cubism and feel like pictorial dead-ends. But this seems an interest that continues to fascinate Hockney, if no longer on canvas and paper than on film, as we saw in his otherwise superb Royal Academy exhibition. But other than that, this is a joyous exhibition of Hockney’s brilliant adventures in print.