At last, the British 'father of Pop art' gets the retrospective he deserves.

Some artists are diminished by major retrospectives, including those artists we consider great. A gap opens up between what you see and what you hear, which is why you can never judge work with your ears, or at least your ears and nothing else. The reassessment – largely subjective, but hopefully an informed and considered subjective – shouldn’t come about because of a few bad or indifferent works, or on the evidence of a gradual failing of powers (even giants sleep, and while the well of creativity may be deep it’s rarely never-ending), but when a whole body of work that follows the arc of a career makes you see that you’ve been relying on your ears all along.

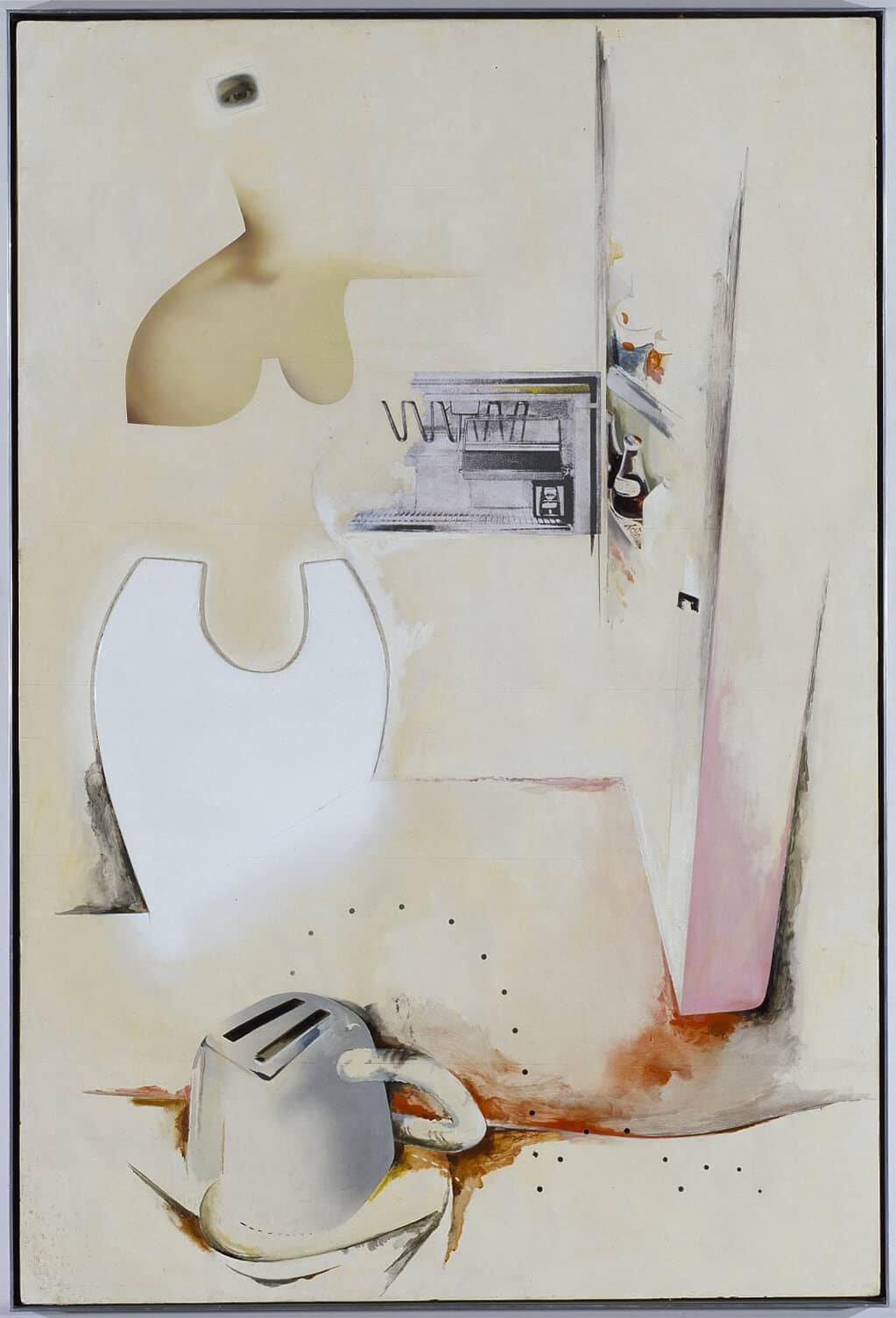

Towards a definitive statements on the coming trends in menswear and accessories (a) 'Together let us explore the stars, 1962; Tate © The Estate of Richard Hamilton

I can think of a few examples at random – Gauguin is one (yes, I think he is), Edward Hopper (not a “giant”, but what verbiage he attracts for a figurative artist with very limited range and imagination and just one or two enduring paintings) is without question another. And having two Lichtenstein surveys in one decade does reinforce how some good ideas should come with their own self-destruct button.

But just as there are artists who disappoint the more you see, there are those who, the more you see, the greater they become. And this despite the works that you’d rather wish they hadn’t done – and there are certainly some of those with regard to Richard Hamilton. There are works that seem too crude, too obvious for his penetrating, analytical mind. But we’ll come to those in a minute.

You have to see a whole body of work by Hamilton to fully appreciate him, and you have to see this retrospective to see that he is even better than the vague “father of British Pop art” esteem we currently hold him in. He’s influential, of course, part of a major zeitgeist-that-was and that extended over some three decades. His influence as a founder member of the Independent Group, a small group of artists and architects, critics and designers who met at the ICA in the Fifties to discuss and disseminate ideas about the newly emergent “consumer culture”, runs deep. His preoccupation with design also ran deep. (Pictured: Interior II, 1968)

But even if he’d ploughed a lonelier furrow, his body of work would reveal what a deeply fascinating artist he was and is. And that’s the only way a major retrospective can succeed – we see that it can’t just be influence, at one or two significant moments of a career, that count, but the body and range of work. A retrospective lays that bare, since you can’t measure influence by any physical contact with the work. What you can measure is how good the actual work is and, in Hamilton’s case, how it’s fed by so many different ideas. Hamilton, that father of British Pop and important pioneer of immersive installation art, is actually so much more.

One of the things that’s so good about this superb retrospective is how many surprises it offers. The Tate has ambitiously set about reconstructing several installations. Opening the exhibition is the earliest, Growth and Form, from 1951 (Hamilton made it as part of an exhibition design for the Festival of Britain). Inspired by the Scottish biologist D’arcy Wentworth Thompson’s On Growth and Form, 1917, a rival theory to Darwin’s Origin of Species, the light-dimmed room presents a strange kind of Surrealist laboratory.

On a grid-based frame plaster models of cell structures loom large, while elsewhere there’s footage of cells dividing, a bubbling test-tube, the skull of a large mammal, eggs from different bird species, and models of molecular structures. A large portrait photograph of an unknown man, simply listed as “Head”, greets you as you enter, nudging you towards ambivalence. The postwar optimism that wanted society made anew, and which included the inexhaustible possibilities of science (and, of course, exemplified by the Festival of Britain) isn’t, I think, presented as a straightforward cause for celebration. There’s a hint – a possible hint – of something of Orwell and Aldous Huxley behind Hamilton’s homage.

Celebration and critique are two approaches that often run parallel in much of Hamilton’s best work, including Fun House, an installation he created with architect John Voelker and artist John McHale for the seminal This is Tomorrow exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery in 1956, an exhibition now only famous for the collage that heralded the birth of Pop art, Hamilton’s Just what is is that makes the modern home so different, so appealing?.

Fun House is plastered with a mash-up of images from Hollywood, sci-fi, advertising and fine art. A bouncy foam carpet gives off a pleasant strawberry odour, and on a spectacular jukebox Fifties hits are spun. Meanwhile, a microphone invites you to “Speak Here”. This is art for the demotic age, with a populace headily seduced by Americana and mass-media culture.

For something more coolly detached (most of Hamilton’s work is a cerebral infusion of cool detachment and implicit critique, and sometimes offered in the guise of art-as-information, that now familiar conceptual trope), the ICA presents two reconstructions of walk-through installations that were both mounted at the institute: Man, Machine and Motion, 1955, and Exhibit, 1957, the latter conceived with Victor Pasmore and critic Lawrence Alloway, and which is something like a 3D Mondrian. The earlier piece, occupying the ICA’s ground floor, presents historical images of different modes of transportation – documentary, diagrammatic, fantastical, speculative – on horizontal and vertical plates mounted on modular grids. Linnaeus fashion, the images are classified according to method of transport. This is image data, rather than empirical data.

Back at the Tate, there is much to ponder and absorb, far too much to outline here. The relationship between sex, machinery and consumerism is just as successfully and wittily explored in the fractured curves and orifices featured in the painting $he, 1958-61 (pictured), as it is in Just what is it…? And then there’s Hamilton’s meticulous reconstruction of Duchamp’s The Large Glass. Duchamp’s influence was a guiding principle in all of Hamilton’s endeavours. But the older artist was assimilated rather than borrowed from, for style and consistency of style was an anathema to Hamilton; it’s an analytical way of thinking that provides the thread that links the work, and that connects it to Duchamp.

Where Hamilton falters is in his later, political work (though his three Northern Ireland paintings, The Citizen, The Subject, and The State, 1982-83, must be his best). He always possessed a pronounced didactic streak, but it was leavened by an appreciation of ambiguity – you can never quite pin the work down – as well as brilliant wit. But seeing Blair dressed as a cowboy, with his hands on his holsters in Shock and Awe, 2010, or a television set seeping blood as it shows images of the first Gulf war, remind me painfully of Harold Pinter’s late foray into anti-war poetry. It’s when the balance tipped in ambiguity’s favour that Hamilton made truly great work. And this is a great, unmissable survey.