Picasso's women and the role they played in his work.

So, Picasso’s last words turned out not to be, “Drink to me. Drink to my health. You know I can’t drink anymore” – yes, those famous last words that inspired a Paul McCartney dirge – but were, according to this TV biography looking at Picasso’s women and how each significant relationship informed the direction of his work, “Get me some pencils”. A more prosaic request, certainly, but he died in bed, aged 93, his pencils delivered and drawing to the last. It was a good and fitting end.

It was, however, an unpromising beginning, for when Picasso entered this world it was feared he was still born. And it seemed a pretty emotionally turbulent middle, too, what with an overlapping parade of women and a vampiric appetite that compelled him to move on to fresh prey with restless abandon.

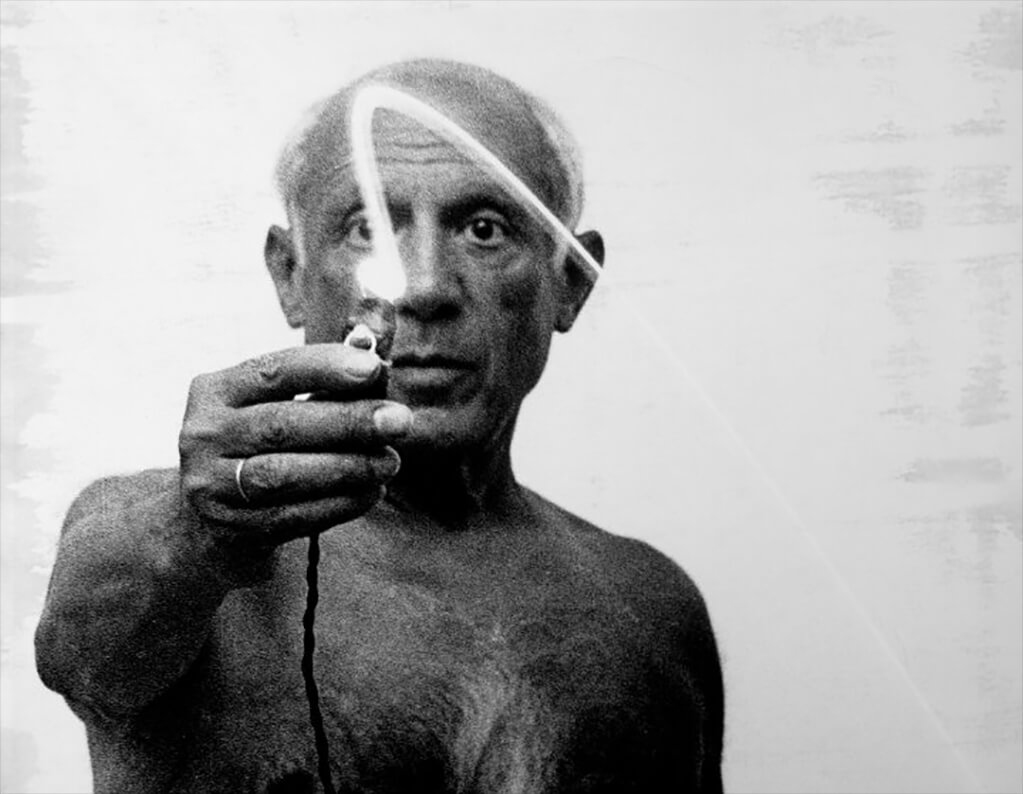

Hugues Nancy’s documentary, with its somewhat schlocky title, sounded not altogether promising, and occasionally the narration got a little breathless, but it was well-researched, talked to all the right people and showed a good selection of archive footage and interviews. So we heard from children and grandchildren, biographers, friends and lovers. John Richardson, Picasso’s most significant English biographer and a friend from the early Fifties until the artist’s death in 1973, talked of first impressions. “The first time I met Picasso,” he recalled, “I was struck by the enormous power that seemed to emanate from this very small man. What struck me was the strong gaze. People from Andalusia think they can have a woman with their eyes – it’s like an extra limb.” Photographs of Picasso, both young and old, show us exactly what Richardson meant.

Françoise Gilot, who came into the artist’s life when she was in her early 20s and he 40 years her senior, told us how everything in his work changed with each woman.“ With each one, she said, “he had a sort of leitmotif. Like Wagner, you can hear the leitmotiv that introduces each character, so with Picasso. My leitmotif,” she added, “was always blue and green.” Later Richardson told us that the beautiful and independent-minded Gilot was the only woman Picasso had ever been involved with who was left undamaged when the relationship ended. She was also the only woman to leave him, rather than the one cast aside.

But in terms of both style and subject matter, the person who was the first to directly influence Picasso’s paintings wasn’t a woman, but a young man, a fellow Catalan by the name of Carles Casagemas, a painter and a poet and close friend, the two almost inseparable in their early years as struggling artists. The first time Picasso travelled to Paris, for the World’s Fair in 1900, was with Casagemas by his side, and the two were soon living together in the ramshackle, bohemian district of Montmarte. When Casemegas committed suicide over a messy relationship with a young model in their circle, Picasso was profoundly affected – though that didn’t stop him later taking up with the model, Germaine.

In the aftermath of Casagemas’s death, Picasso painted the dead young poet lying in his coffin, the palette limited to icy hues and a blue tonality. Whereas before he’d been a veritable magpie, incorporating into his work Impressionism, pointillism, and Art Nouveau, often with an acid bright palette, his friend’s death precipitated Picasso’s significant Blue Period. Casagemas and Germaine would reappear in later works, too, notably The Three Dancers of 1925 (Tate), a fraught and terrifying danse macabre.

The film went through each of the important women in his life, using ample pictorial illustrations. But there were significant omissions and fudges, notably involving his difficult relationship with his children. Perhaps this was because of the involvement in the film’s production of Olivier Widmaier Picasso, Picasso grandson with Marie-Thérèse, the young woman who would give rise to such erotic masterpieces as the 1932 Le Rêve. The grandson got a filmmaking credit alongside Nancy. Perhaps worse was the occasionally careless way the documentary discussed the work, remarkably managing a lengthy discussion on the birth of Cubism without once mentioning Cézanne.

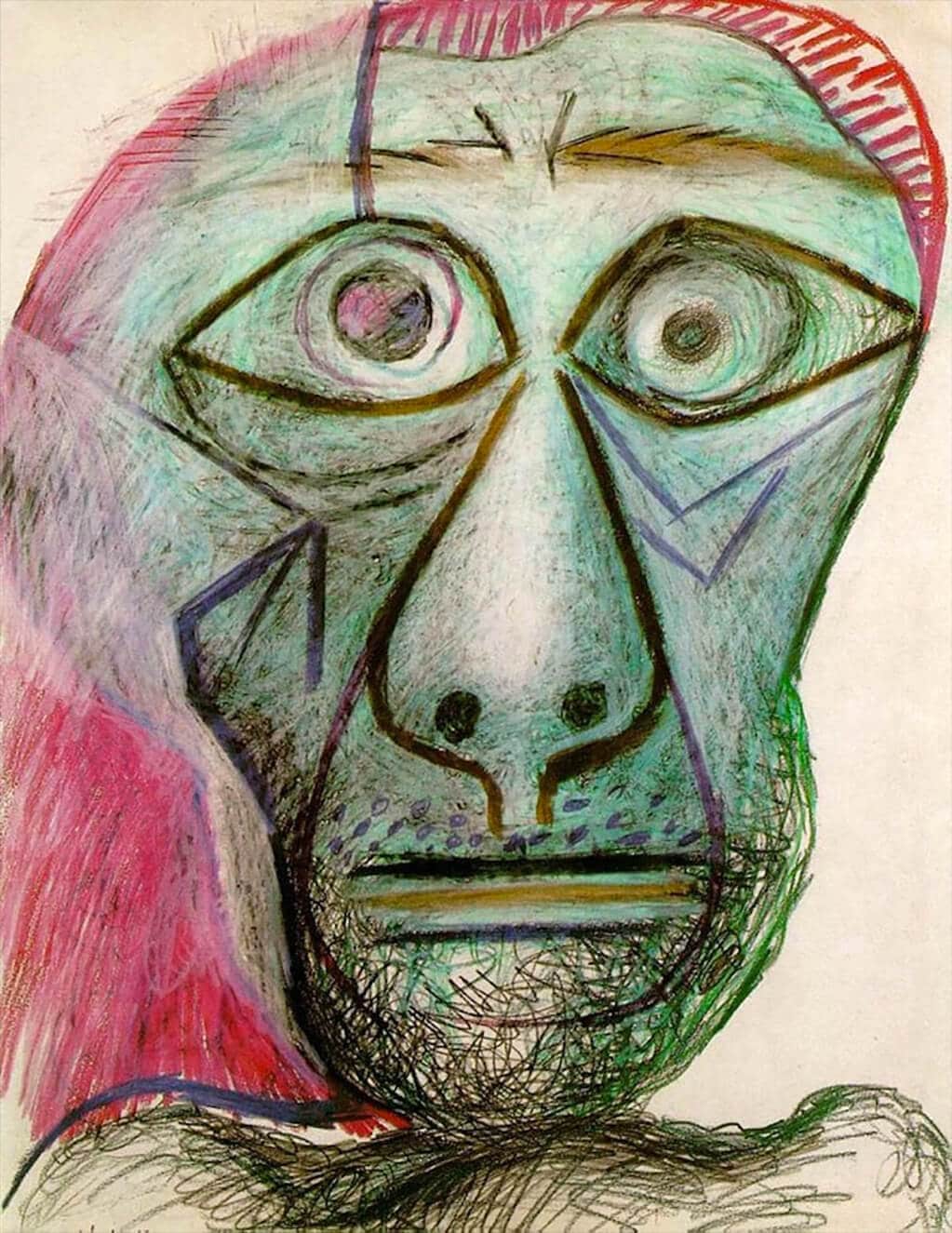

Nonetheless there were plenty of interesting insights and the end of the film was deeply moving. Biographer Pierre Daiz talked of visiting the artist at his home very near the end of his life. Picasso took him to look at his last self portrait, laid out on a chaise lounge “like a person”. This raw, powerful and devastating portrait (pictured) is of a face etched with painful uncertainty.