The complete series of the artist's masterful etchings.

The Vollard Suite is Picasso’s most celebrated series of etchings. Named after Ambroise Vollard, the influential avant-garde art dealer who gave the 19-year-old Picasso his first exhibition in Paris in 1901, the series was commissioned by the dealer in 1930. For the next seven years Picasso worked on it in creative bursts, completing a series of 100 etchings. Last autumn, one of the complete set – a total of 310 were printed – was purchased by London-based private collector Hamish Parker as a gift to the British Museum.

Since the series has never previously been shown in its entirety in the UK, this exhibition is an exciting first. But the series wasn’t always held in such high esteem. In fact, this isn’t the first time the suite was made available to the British Museum: given the option to buy the series for £1,900 in 1955, the museum declined.

Even at that late date – the age of the celebrity of Henry Moore, whose work was directly influenced by his older Spanish contemporary – conservative attitudes to the European avant-garde, and to modernism in general, abounded in the higher echelons of the British art establishment. But now the Vollard Suite can be seen amongst a few choice etchings by Rembrandt, the undisputed master of the form, as well as a small selection by Goya, the fellow Spaniard who chronicled the evils of war and superstition. Picasso is greatly indebted to both artists (among the suite are some wonderfully exuberant caricatures of the 17th-century Dutch artist). Ingres, is here, too, for Picasso greatly admired the French artist’s fine line and his sensual depictions of women; as are some examples of Greek sculpture. It was during this period that Picasso looked foremost to Classical antiquity.

But many of the most intense phases of Picasso’s creative output can also be linked to the women in his life. Certainly Picasso seemed to renew himself with a kind of vampiric zeal during his most passionate entanglements. When Picasso embarked on the Vollard Suite he was already involved with Marie-Thérèse Walter: two years earlier Picasso had been stopped in his tracks by Walter’s classical features when he spotted her outside a Parisian department store – she was 17, he 45 and married. When the suite came to an end the relationship, with Walter having newly given birth, was already petering out (he had taken up with Dora Maar, the Surrealist photographer who was to inspire The Weeping Woman). But Walter was to inspire many of Picasso’s greatest paintings, as well as these masterful etchings.

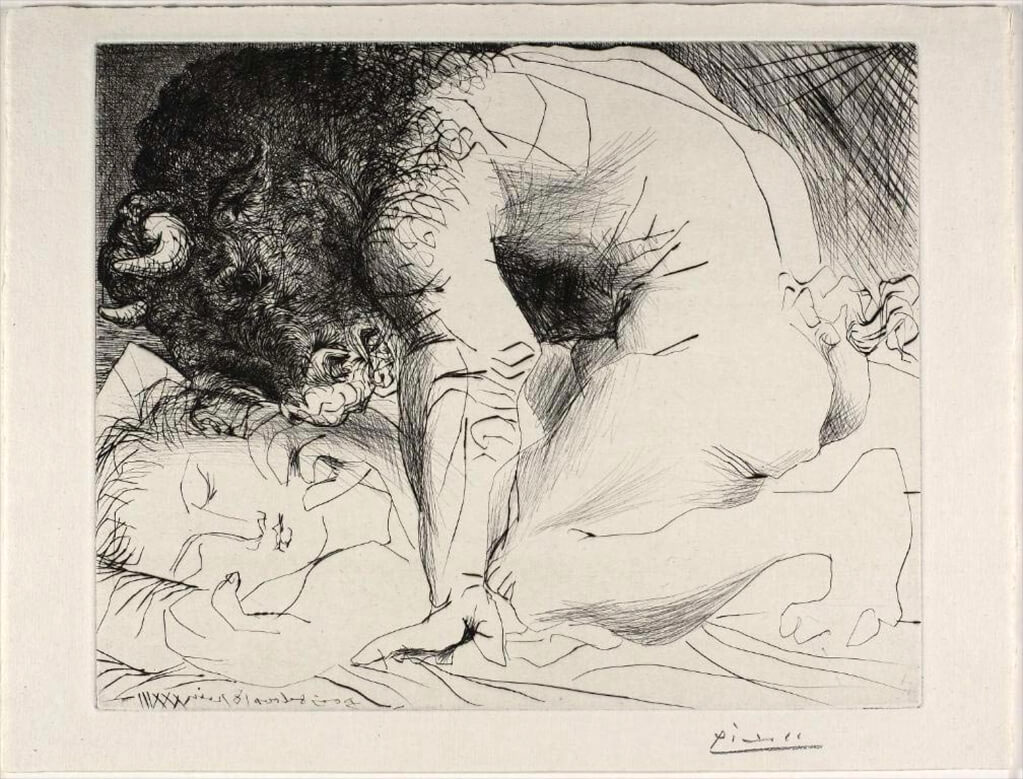

And so she appears in print after print of the Vollard Suite, as artist’s muse, as lover, as child, and as Pygmalion sculpture awakening as human flesh. Picasso appears himself as the bearded, sage-like sculptor of classical antiquity, or in later, more turbulent and sexually charged scenes, in the guise of a Herculean figure ravaging his innocent love. In a later series of prints, entitled “Rape” by an early cataloguer, we see an even more feverish response to his muse. Picasso, a hulking creature who is now more beast than man, overwhelms his mistress with his muscular bulk, while she resembles little more than a broken doll.

And in some of the most arresting images of the series we find Picasso’s sexually predatory alter-ego in the Minotaur (pictured above: Minotaur Caressing a Sleeping Woman, 1934), a dumb, brutish creature in which tenderness and vulnerability are also evident. These finally lead us to the Blinded Minotaur works of the series. Encountering scenes such as the dreamlike Blind Minotaur Led by a Little Girl in the Night, 1937 (pictured at the top of this article), we find this beast of classical mythology now helpless and impotent, but still remaining a powerful physical presence. Raising his head to the night sky he appears to soundlessly howl. In these deeply autobiographical works we encounter direct precursors to Picasso’s great anguished masterpiece of war, Guernica.