Did American painting exist before Abstract Expressionism? Not such a daft question if we don't get to see any of it.

The National Gallery recently embarked on a first: they acquired their first American painting. Men of the Docks, 1912, may not be George Bellows’ most famous or best-regarded work; nonetheless, it’s a gritty and beautifully observed slice of New York life among the city’s dockside workers.

“In this country, we have no need of art as culture,” Bellows’ former tutor, the artist Robert Henri, pronounced. “No need of art for poetry’s sake….What we do need is art that expresses the spirit of the people today.” Bellows absorbed Henri’s lesson and absorbed it well, at least during the first half of his career (his career took a strange turn after that, and then he died aged just 42).

But until two recent exhibitions in London – a small National Gallery survey in 2011 of the New York Ashcan school of which Bellows was a leading member, and a second survey focusing on Bellows at the Royal Academy last year – few gallery-goers had even heard of him. Should anyone be surprised?

There’s such a paucity of pre-postwar American art in UK public collections you’d almost think American painting – by which I mean work rooted, more or less, in American ideas, American themes, preoccupations, place, experience – didn’t exist before Abstract Expressionism. Or before Pollock dripped his first can of paint in 1947. But then we do tend to think in big movements. (We don’t think this way about the history of literature, but then literature isn’t a collectable commodity.)

Many will still argue that American painting before mid-century, with just a few exceptions, is really too derivative, too backward-looking to get excited about, and that it was photography that American artists really excelled at in the first half of this century. Furthermore, it was the intellectual exodus from Europe to New York before the outbreak of the Second World War that really gave American art its injection of life-blood.

American photographers certainly excelled. But here’s a selection of paintings by artists who also excelled in the first few decades of the 20th century – though not all follow the precept of being rooted in American experience etc. A number are, of course, still extremely well-known. Many were part of an avant-garde circle clustered around the influential gallerist and photographer Alfred Steiglitz. All worked, at least in the early part of their careers, in New York or around the East Coast, while only one worked from beginning to end outside the avant-garde altogether, in America’s Midwest.

Arthur Dove: Abstraction No.2 (1910-11)

The prize for Western art’s first abstract painting, long claimed for a 1911 painting, now lost, by Kandinsky, is contested ground (though it seems mystical Swedish painter Hilma af Klint beat Kandinsky to it by some five years). But at a time when most American artists were barely catching up with Impressionism, Arthur Dove was, as John Updike put it, “a pioneer of abstract painting, but not one of its heroes”. Like many avant-garde American artists of the period, including Georgia O’Keefe, who was greatly influenced by him, Dove came under the wing and patronage of gallerist and photographer Alfred Steiglitz. This tiny painting, like most of Dove’s work, takes its cue from the observed world, and is therefore not a a pure “non-representational” painting. But it comes pretty close.

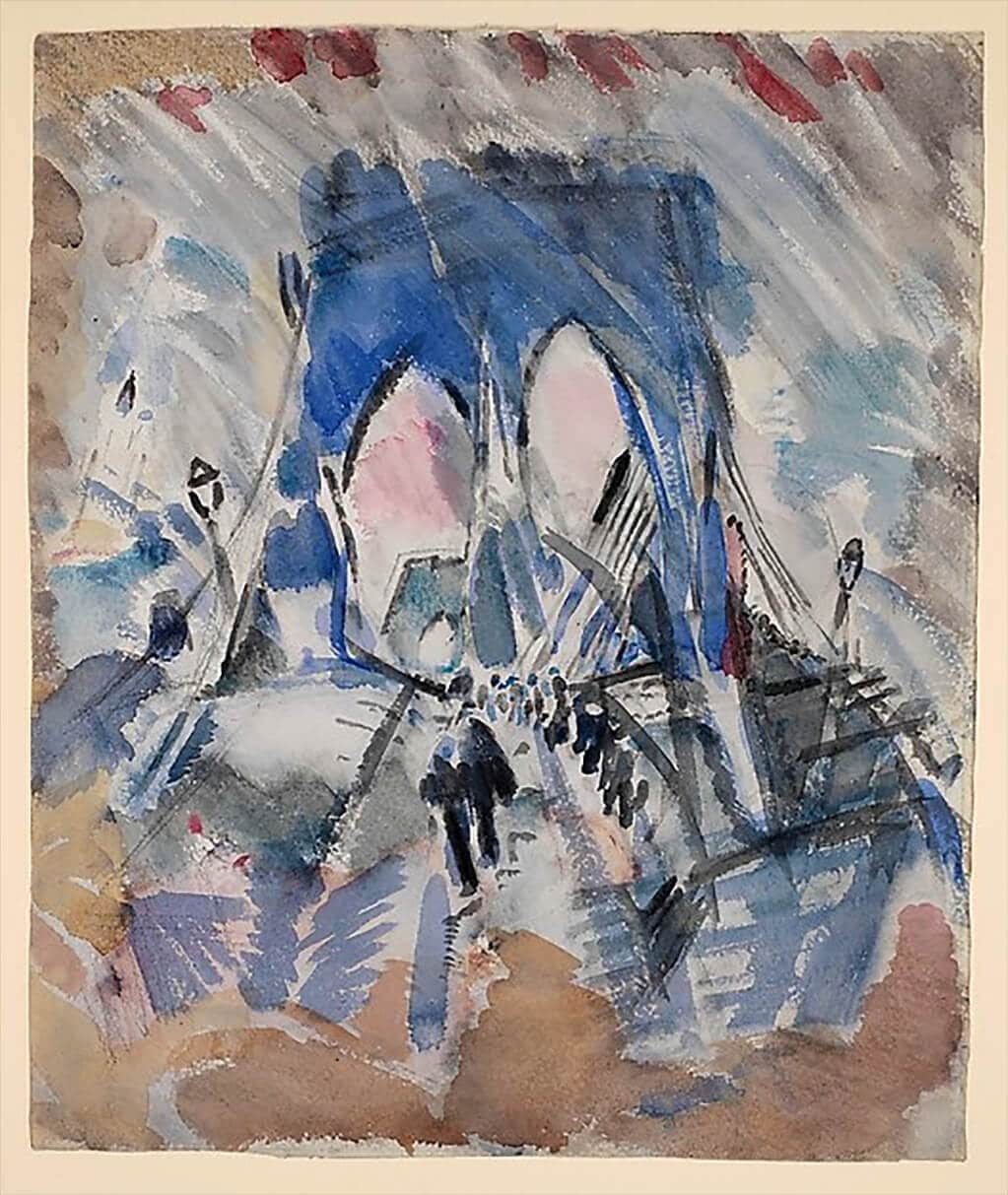

John Marin: Brooklyn Bridge (1912)

John Marin was a big artist in his day and another Steiglitz protégé. His loose handling of paint, and his use of watercolour to blur objects under hazy washes while leaving stretches of paper and canvas untouched, lent his paintings an exhilarating sense of freedom and spontaneity. Said to have greatly influenced the Abstract Expressionists, he was among many modern artists drawn to depicting Brooklyn Bridge. Here it’s rendered as if it’s rearing up untethered and about to float weightlessly up into the atmosphere.

Marsden Hartley: Portrait of a German Officer (1914)

The Maine-born artist visited Berlin in 1913 and was so enamoured by the military parades of the imperial guard that he moved there later that year. He also mixed in the city’s avant-garde circles, getting to know Kandinsky and Franz Marc. In the German male, he found an embodiment of the erotic masculine ideal (as opposed, according to him, the weedy French specimens he encountered on an earlier visit to Paris). He became close to a Prussian lieutenant, Karl von Freyburg, who, after receiving the Iron Cross, was killed near Amiens. This painting, among a series of 14, is a bold arrangement of military symbols, insignia and patterns – the black and white checks may, for instance, suggest Freyburg’s love of chess – against a strong black ground. By employing what he called “intuitive abstraction,” war motifs and other symbols became the language Hartley used to express his grief.

Georgia O’Keeffe: Evening Star V (1917)

Like many of the artists on this list, O’Keeffe was part of Alfred Steiglitz’s circle – indeed, she married him. Largely known for her slickly polished paintings of vaginal flowers, O’Keeffe’s earlier work, under the influence of Dove, came closer to non-representational painting, though as the title of this work indicates her paintings remained steadfastly rooted in nature. O’Keefe painted a series of Evening Star watercolours, employing a limited but bold and seductive palette and creating shapes that suggest mystical hieroglyphs. The paintings of Robert and Sonia Delaunay, with their abstract light- and colour-infused Orphism, also come to mind.

Joseph Stella: Brooklyn Bridge (1919)

Joseph Stella was an Italian émigré, who arrived in New York to study medicine but quickly abandoned his studies to take up painting. Becoming increasingly homesick, he returned to Europe in 1909, where he associated with Cubist and Futurist artists. When he eventually returned to the States in 1912 he developed an obsession with Brooklyn Bridge, that icon of industrial modernity. Having absorbed the lessons of Futurism, he set about creating a series of dynamic modernist “altarpieces” that somewhat resemble stained glass. This is among the first he painted.

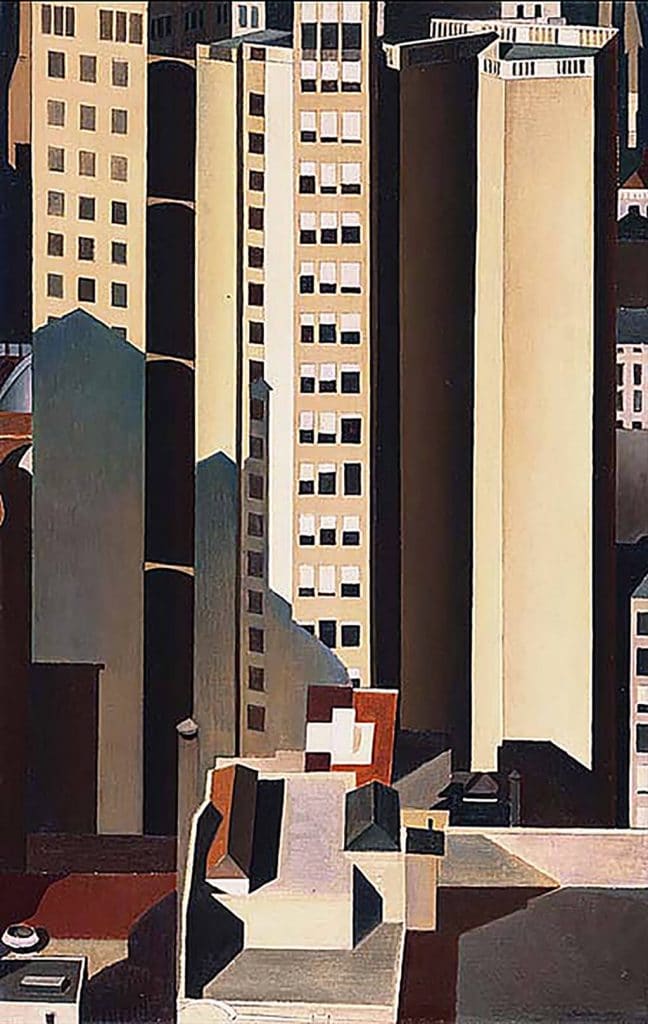

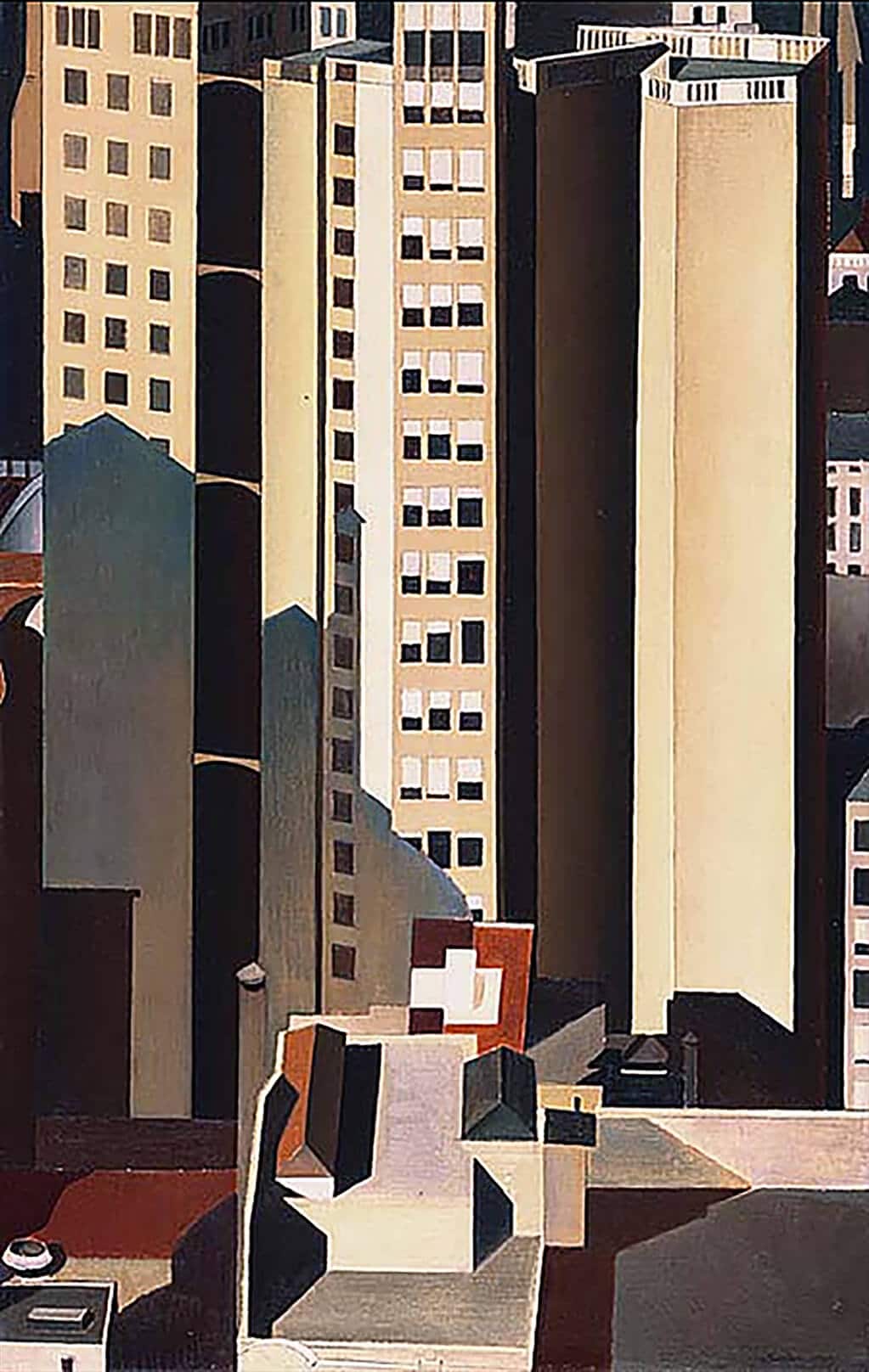

Charles Sheeler: Skyscrapers (1922)

As well as being a painter associated with American Precisionism, Sheeler was an acclaimed photographer. Indeed, he’s the original “multi-media” artist. The year before he painted this picture of dramatically imposing and abutting New York skyscrapers, he made a short film with fellow photographer Paul Strand. With intertitles of quotes by Walt Whitman, Manhatta lovingly documents the working life of the city and its busy waterfront. You will see that the film, as well as his photographs, influenced the way he conceived and composed his paintings, even though his industrial and urban canvases are, by contrast, always devoid of people. Lines are precisely delineated, forms are simplified, block shadows are cast, and buildings look bleached out by a merciless sun. By eliminating the horizon, the buildings are rendered even more oppressive and inhuman in scale.

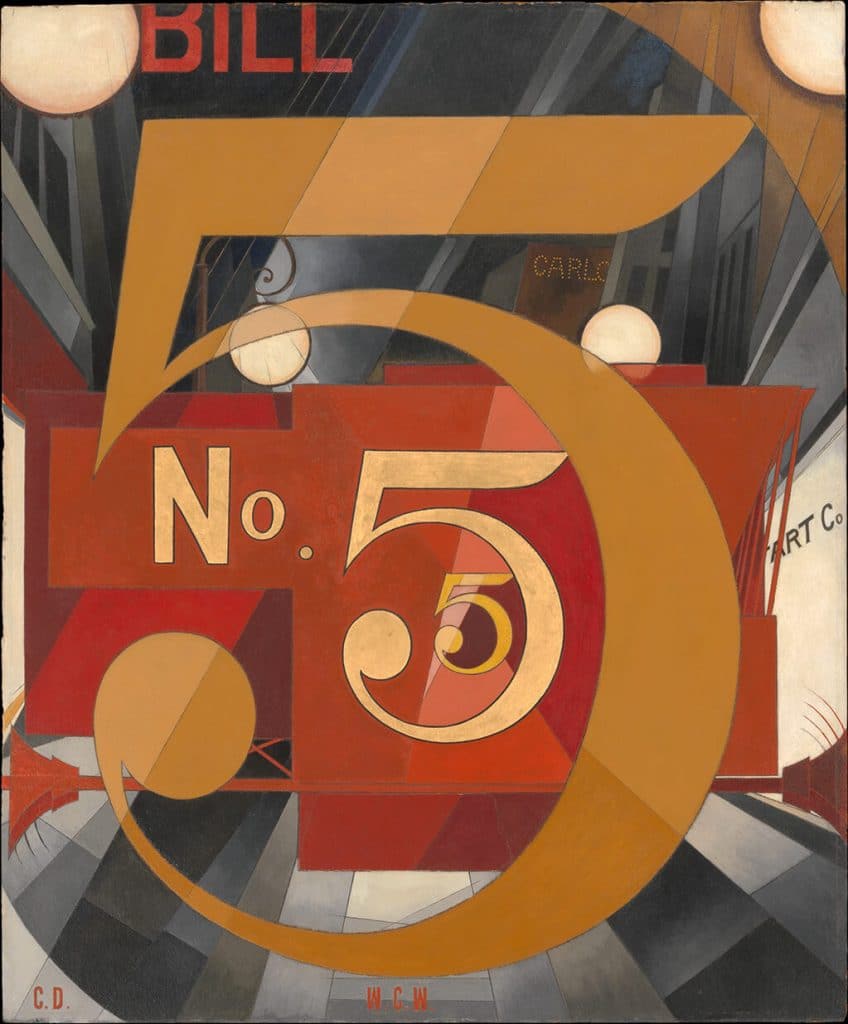

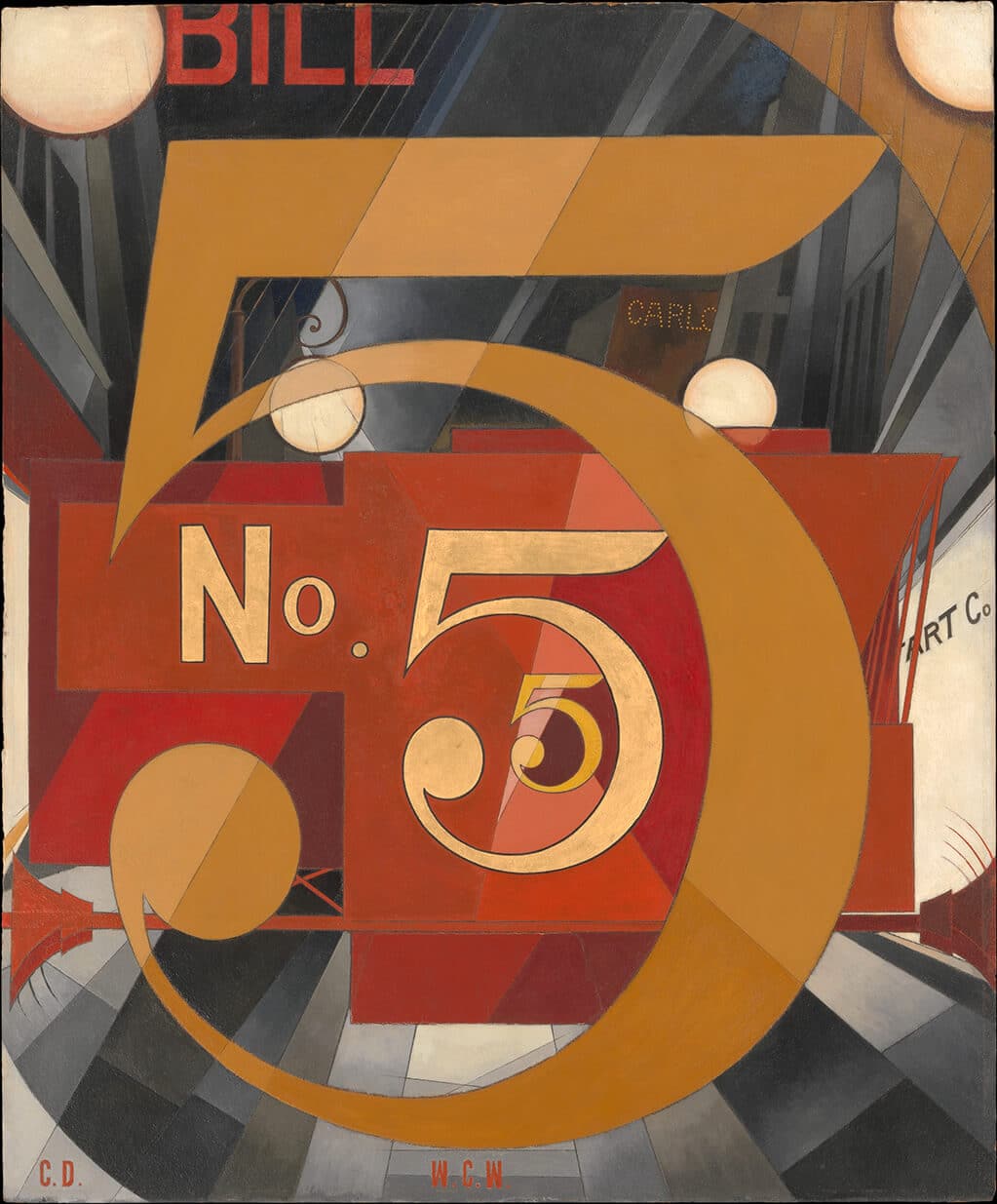

Charles Demuth: I Saw the Figure in Gold (1928)

Demuth painted a series of modernist “portraits” of his artistic friends (O’Keefe, Dove, Hartley and Marin among them) in which each employs motifs from the subject’s work. This painting – his best and most famous – is a witty transliteration of a line from William Carlos Williams’ poem The Great Figure, in which the Imagist poet sees the figure 5 in gold against a red fire truck moving towards him. The dynamic lines and rays of colour and light embody a celebratory mood. This is a homage to both friend and to the dynamic, quintessentially 20th-century city that is New York.

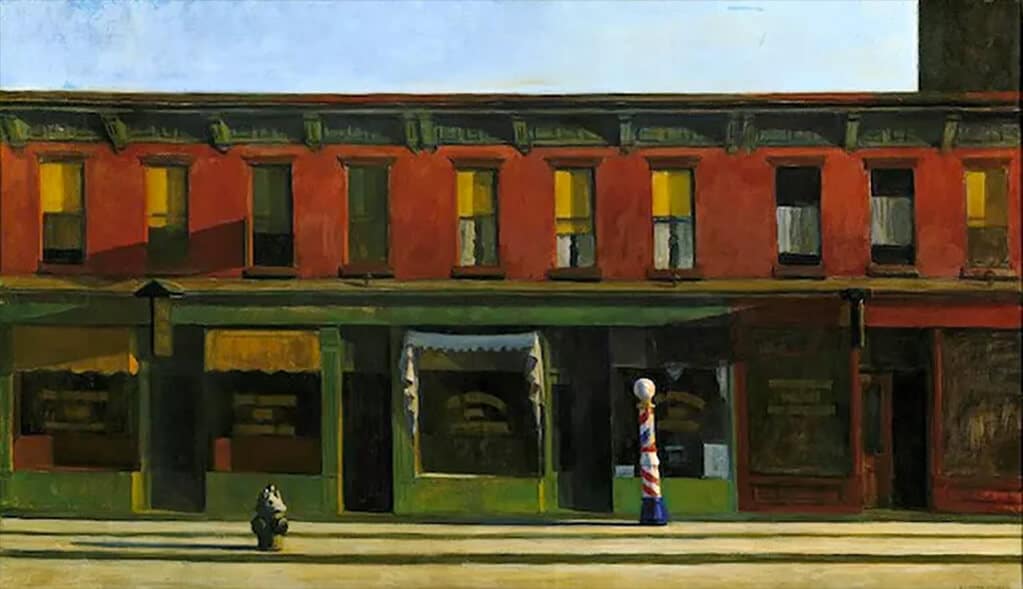

Edward Hopper: Early Sunday Morning (1930)

Too many Hoppers in the flesh will make you see how limited a painter he actually was and how many of his paintings look better in reproduction, but his impenetrably silent, noir-ish scenes have obviously embedded themselves in the American psyche. Hopper spent much of his life as a commercial illustrator, and then was briefly associated with the New York Ashcan school, alongside Bellows. He was popular during his lifetime, as he is popular now. This view of a street with its two-tiered redbrick building is ordinary and yet not ordinary. Its silent windows, its darkened shop fronts, and its long shadows make it tremble on the edge of something almost surreal – but not quite. It’s a painting on the cusp of something, but it betrays nothing.

Grant Wood: Daughters of the Revolution (1932)

Wood painted that Mona Lisa of American Regionalist painting, American Gothic. Two years later he painted Daughters of the Revolution, which he claimed was his only satirical painting. Unlike the East Coast avant-garde artists on this list, Wood was a Midwesterner, and his subject matter was fiercely wedded to the life and the land that surrounded him, albeit through a fictionalising lens. Daughters is a delightfully comic painting in which three aged spinsters – the unadorned left hand holding the tea cup is a central focus of the picture – pose in front of a reproduction of Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze’s grand history painting of the American Revolution, Washington Crossing the Delaware. Small-town depression-era conservatism is the bastard offspring of Revolutionary ideals indeed.

Stuart Davis: New York Waterfront (1938)

Davis was a huge jazz fan. Its freewheeling modern rhythms infuse his paintings. He absorbed all the formal lessons of Matisse and Picasso, and yet his paintings appear to embody all that is American, at least for the urbane sophisticate. His jumpy, bright, hard-edged style – cool yet hot – feels exactly like American painting should feel in the age of swing and jazz – optimistic, full of zip and swagger – before Abstract Expressionism boots it out. As its title states, the painting depicts a New York scene, but a New York suggestive of its spirit and imagination (its genius loci), which goes beyond physical appearance.